close

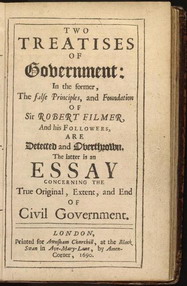

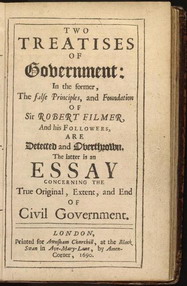

今天在網路上閒晃的時候,無意之中看見有人提到「洛克」(John Locke)的名字。於是,一時興起,就來個溫故知新吧!說起洛克,經過國中和高中兩次歷史洗禮,啟蒙運動之中,「洛克」、「孟德斯鳩」和「盧梭」的學說,從「天賦人權」、「三權分立」、「主權在民」,一點一點慢慢建立起西方現代民主的根基。某些考題裡面,這些都是很重要的必背應考資訊。尤其「主權在民」的學說可是後來影響了法國大革命和美國獨立革命。就連咱們中華民國憲法的第一條和第二條也說,「中華民國基於三民主義,為民有民治民享之民主共和國。中華民國之主權屬於國民全體。」很明顯地,就是在說明中華民國也是建立在「主權在民」這個觀念上的。雖然說洛克先生並不是一個非常有一貫性的哲學大師,但是他有一篇政治學論文卻是非常有名的!那就是在1689年出版的「政府論」(Two Treatises Of Government)。

在這個紛紛擾擾的時刻,閱讀洛克的政府論卻著實讓人覺得「人家的著作可以在三百一十七年就點名清楚現在的情形,果然是有其在學術上的權威性!」這其實也不算是預言,只是很清楚地點明政府以及人民之間的權利、義務關係。在政府論的上篇,洛克主要是對抗「君權神授」的理論;在下篇之中,洛克則在闡揚自然權利、社會契約、政治體制和自由法治等思想理論。我把下篇十九章的目錄列出來:

1. (承接上篇,開始敘述政治權力。)

2. 論自然狀態

3. 論戰爭狀態

4. 論奴役

5. 論財產

6. 論父權

7. 論政治的或公民的社會

8. 論政治社會的起源

9. 論政治社會和政府的目的

10. 論國家的形式

11. 論立法權的範圍

12. 論國家的立法權、執法權和對外權

13. 論國家權力的統屬

14. 論特權

15. 綜論父權、政治權力和專制權力

16. 論征服

17. 論篡奪

18. 論暴政

19. 論政府的解體

這一連串看下來,有點頭昏眼花了吧!我們直接跳進最後一章去看,倒是可以看見許多會讓人不覺莞爾的會心微笑。之前,不是有某某黨的黨主席說了,如果誰誰誰被罷免下台,國家會亂嗎?我們可愛的洛克先生在三百一十七年前就已經賞了這個某某黨的黨主席一個甜蜜的耳光。(所以那位某某黨的黨主席好像應該要回家去唸唸書才對。)某位創造出「轉型正義」的偉大人士的論點也可以直接在這裡被洛克先生教訓一頓。(看來也是可以套句陳文茜以前常說的話,「回去唸唸書再來說吧!」)

所以說,如果歐美的民主素養在三百年前開始締造,經過了這些時間發展,終於建設出來一個還算有模有樣的格局;那麼我們的民主素養需要怎樣鍛鍊才能夠「趕美超英」呢?這其實真的是教育和民族性格養成的大問題!

現在台灣倒扁的活動正熱,據說大家都用「你匯了一百元了嗎?」來當問候語了!(真的還假的呀?)不過,當我在BBS上有樣學樣,這樣問候看我個人版面的朋友的時候,倒還沒有誇張到每個人都義憤填膺地去匯了款。對於我這個拿中華民國台灣護照,按照中華民國的稅法繳中華民國所得稅,享有中華民國公民權的人,我倒覺得不管匯不匯一百元,倒扁還是挺扁,都應該要把自己論述的來龍去脈整理清楚。(也就是說,如果只是一時氣憤只跟著別人大喊倒扁還是挺扁的人,不如拿一百元去買本政府論次講來好好充實一下所謂的「民主素養」還比較划算!真的,誠品網路書店裡,正港資訊文化事業有限公司出版的「洛克:政府論次講」才索價新台幣一百一十七元而已!)

如果要看免錢版的,孤狗大神也有求必應呀!

中文:http://easysea.net/zongjiao/luoke-zfl/index.htm (瞿菊農、葉啟芳譯本)

英文:http://www.constitution.org/jl/2ndtreat.htm

我摘錄一些讓我看的會心一笑的地方吧!(不過,先說一聲,以下可是很知青自high地摘錄自中文譯本和英文版本喔!)

「公民社會是它的成員之間的一種和平狀態,由於他們有立法機關作為仲裁者來解決可能發生於他們任何人之間的一切爭執,戰爭狀態就被排除了;因此,一個國家的成員是通過立法機關才聯合並團結成為一個協調的有機體的。立法機關是給予國家以形態、生命和統一的靈魂;分散的成員因此才彼此發生相互的影響、同情和聯繫。所以,當立法機關被破壞或解散的時候,隨之而來的是解體和消亡。因為,社會的要素和結合在於有一個統一的意志,立法機關一旦為大多數人所建立時,它就使這個意志得到表達,而且還可以說是這一意志的保管者。」(第212條)

Civil society being a state of peace, amongst those who are of it, from whom the state of war is excluded by the umpirage, which they have provided in their legislative, for the ending all differences that may arise amongst any of them, it is in their legislative, that the members of a commonwealth are united, and combined together into one coherent living body. This is the soul that gives form, life, and unity, to the common-wealth: from hence the several members have their mutual influence, sympathy, and connexion: and therefore, when the legislative is broken, or dissolved, dissolution and death follows: for the essence and union of the society consisting in having one will, the legislative, when once established by the majority, has the declaring, and as it were keeping of that will. (Art. 212)

「人們參加社會的理由在於保護他們的財產;他們選擇一個立法機關並授以權力的目的,是希望由此可以制定法律、樹立準則,以保衛社會一切成員的財產,限制社會各部分和各成員的權力並調節他們之間的統轄權。因為決不能設想,社會的意志是要使立法機關享有權力來破壞每個人想通過參加社會而取得的東西,以及人民為之使自己受制於他們自己選任的立法者的東西;所以當立法者們圖謀奪取和破壞人民的財產或貶低他們的地位使其處於專斷權力下的奴役狀態時,立法者們就使自己與人民處於戰爭狀態,人民因此就無需再予服從,而只有尋求上帝給予人們抵抗強暴的共同庇護。所以,立法機關一旦侵犯了社會的這個基本準則,並因野心、恐懼、愚蠢或腐敗,力圖使自己握有或給予任何其他人以一種絕對的權力,來支配人民的生命、權利和產業時,他們就由於這種背棄委託的行為而喪失了人民為了極不相同的目的曾給予他們的權力。這一權力便歸屬人民,人民享有恢復他們原來的自由的權利,並通過建立他們認為合適的新立法機關以謀求他們的安全和保障,而這些正是他們所以加入社會的目的。我在這裏所說的一般與立法機關有關的話也適用於最高的執行者,因為他受了人民的雙重委託,一方面參與立法機關又同時擔任法律的最高執行者,因此當他以專斷的意志來代替社會的法律時,他的行為就違背了這兩種委託。

假使他運用社會的強力、財富和政府機構來收買代表,使他們服務於他的目的,或公然預先限定選民們要他們選舉他曾以甘言、威脅、諾言或其他方法收買過來的人,並利用他們選出事前已答應投什麼票和制定什麼法律的人,那麼他的行為也違背了對他的委託。這種操縱候選人和選民並重新規定選舉方法的行為,豈不就是意味著從根本上破壞政府和毒化公共安全的本源嗎?因為,既然人民為自己保留了選擇他們的代表的權利,以保障他們的財產,他們這樣做不過是為了經常可以自由地選舉代表,而且被選出的代表按照經過審查和詳盡的討論而確定的國家和公共福利的需要,可以自由地作出決議和建議。那些在未聽到辯論並權衡各方面的理由以前就進行投票的人們,是不能做到這一點的。佈置這樣的御用議會,力圖把公然附和自己意志的人們來代替人民的真正代表和社會的立法者,這肯定是可能遇到的最大的背信行為和最完全的陰謀危害政府的表示。如果再加上顯然為同一目的而使用酬賞和懲罰,並利用歪曲法律的種種詭計,來排除和摧毀一切阻礙實行這種企圖和不願答應和同意出賣他們的國家的權利的人們,這究竟是在幹些什麼,是無可懷疑的了。

這些人用這樣的方式來運用權力,辜負了社會當初成立時就賦予的信託,他們在社會中應具有哪種權力,是不難斷定的;並且誰都可以看出,凡是曾經試圖這樣做的人都不會再被人所信任。」(第222條)

The reason why men enter into society, is the preservation of their property; and the end why they choose and authorize a legislative, is, that there may be laws made, and rules set, as guards and fences to the properties of all the members of the society, to limit the power, and moderate the dominion, of every part and member of the society: for since it can never be supposed to be the will of the society, that the legislative should have a power to destroy that which every one designs to secure, by entering into society, and for which the people submitted themselves to legislators of their own making; whenever the legislators endeavour to take away, and destroy the property of the people, or to reduce them to slavery under arbitrary power, they put themselves into a state of war with the people, who are thereupon absolved from any farther obedience, and are left to the common refuge, which God hath provided for all men, against force and violence. Whensoever therefore the legislative shall transgress this fundamental rule of society; and either by ambition, fear, folly or corruption, endeavour to grasp themselves, or put into the hands of any other, an absolute power over the lives, liberties, and estates of the people; by this breach of trust they forfeit the power the people had put into their hands for quite contrary ends, and it devolves to the people, who have a right to resume their original liberty, and, by the establishment of a new legislative, (such as they shall think fit) provide for their own safety and security, which is the end for which they are in society. What I have said here, concerning the legislative in general, holds true also concerning the supreme executor, who having a double trust put in him, both to have a part in the legislative, and the supreme execution of the law, acts against both, when he goes about to set up his own arbitrary will as the law of the society. He acts also contrary to his trust, when he either employs the force, treasure, and offices of the society, to corrupt the representatives, and gain them to his purposes; or openly pre-engages the electors, and prescribes to their choice, such, whom he has, by solicitations, threats, promises, or otherwise, won to his designs; and employs them to bring in such, who have promised before-hand what to vote, and what to enact. Thus to regulate candidates and electors, and new-model the ways of election, what is it but to cut up the government by the roots, and poison the very fountain of public security? for the people having reserved to themselves the choice of their representatives, as the fence to their properties, could do it for no other end, but that they might always be freely chosen, and so chosen, freely act, and advise, as the necessity of the common-wealth, and the public good should, upon examination, and mature debate, be judged to require. Thus, those who give their votes before they hear the debate, and have weighed the reasons on all sides, are not capable of doing. To prepare such an assembly as this, and endeavour to set up the declared abettors of his own will, for the true representatives of the people, and the law-makers of the society, is certainly as great a breach of trust, and as perfect a declaration of a design to subvert the government, as is possible to be met with. To which, if one shall add rewards and punishments visibly employed to the same end, and all the arts of perverted law made use of, to take off and destroy all that stand in the way of such a design, and will not comply and consent to betray the liberties of their country, it will be past doubt what is doing. What power they ought to have in the society, who thus employ it contrary to the trust went along with it in its first institution, is easy to determine; and one cannot but see, that he, who has once attempted any such thing as this, cannot any longer be trusted. (Art. 222)

「這種革命不是在稍有失政的情況下就會發生的。對於統治者的失政、一些錯誤的和不適當的法律和人類弱點所造成的一切過失,人民都會加以容忍,不致反抗或口出怨言的。但是,如果一連串的濫用權力、瀆職行為和陰謀詭計都殊途同歸,使其企圖為人民所了然——人民不能不感到他們是處於怎樣的境地,不能不看到他們的前途如何——則他們奮身而起,力圖把統治權交給能為他們保障最初建立政府的目的的人們,那是毫不足怪的。如果沒有這些目的,則古老的名稱和美麗的外表都決不會比自然狀態或純粹無政府狀態來得好,而是只會壞得多,一切障礙都是既嚴重而又咄咄逼人,但是補救的辦法卻更加遙遠和難以找到。」(第225條)

Such revolutions happen not upon every little mismanagement in public affairs. Great mistakes in the ruling part, many wrong and inconvenient laws, and all the slips of human frailty, will be born by the people without mutiny or murmur. But if a long train of abuses, prevarications and artifices, all tending the same way, make the design visible to the people, and they cannot but feel what they lie under, and see whither they are going; it is not to be wondered, that they should then rise themselves, and endeavour to put the rule into such hands which may secure to them the ends for which government was at first erected; and without which, ancient names, and specious forms, are so far from being better, that they are much worse, than the state of nature, or pure anarchy; the inconveniencies being all as great and as near, but the remedy farther off and more difficult. (Art. 225)

「但是,如果那些認為我的假設會造成叛亂的人的意思是:如果讓人民知道,當非法企圖危及他們的權利或財產時,他們可以無須服從,當他們的官長侵犯他們的財產、辜負他們所授與的委託時,他們可以反抗他們的非法的暴力,這就會引起內戰或內部爭吵;因此認為這一學說既對世界和平有這種危害性,就是不可容許的。如果他們抱這樣的看法,那麼,他們也可以根據同樣的理由說,老實人不可以反抗強盜或海賊,因為這會引起紛亂或流血。在這些場合倘發生任何危害,不應歸咎於防衛自己權利的人,而應歸罪於侵犯鄰人的權利的人。假使無辜的老實人必須為了和平乖乖地把他的一切放棄給對他施加強暴的人,那我倒希望人們設想一下,如果世上的和平只是由強暴和掠奪所構成,而且只是為了強盜和壓迫者的利益而維持和平,那麼世界上將存在什麼樣的一種和平。當羔羊不加抵抗地讓兇狠的狼來咬斷它的喉嚨,誰會認為這是強弱之間值得贊許的和平呢?」(第228條)

But if they, who say it lays a foundation for rebellion, mean that it may occasion civil wars, or intestine broils, to tell the people they are absolved from obedience when illegal attempts are made upon their liberties or properties, and may oppose the unlawful violence of those who were their magistrates, when they invade their properties contrary to the trust put in them; and that therefore this doctrine is not to be allowed, being so destructive to the peace of the world: they may as well say, upon the same ground, that honest men may not oppose robbers or pirates, because this may occasion disorder or bloodshed. If any mischief comes in such cases, it is not to be charged upon him who defends his own right, but on him that invades his neighbours. If the innocent honest man must quietly quit all he has, for peace sake, to him who will lay violent hands upon it, I desire it may be considered, what a kind of peace there will be in the world, which consists only in violence and rapine; and which is to be maintained only for the benefit of robbers and oppressors. Who would not think it an admirable peace betwixt the mighty and the mean, when the lamb, without resistance, yielded his throat to be torn by the imperious wolf? (Art. 228)

「我承認,私人的驕傲、野心和好亂成性有時曾引起了國家的大亂,黨爭也曾使許多國家和王國受到致命的打擊。但禍患究竟往往是由於人民的放肆和意欲擺脫合法統治者的權威所致,還是由於統治者的橫暴和企圖以專斷權力加諸人民所致,究竟是壓迫還是抗命最先導致混亂,我想讓公正的歷史去判斷。我相信,不論是統治者或臣民,只要用強力侵犯君主或人民的權利,並種下了推翻合法政府的組織和結構的禍根,他就嚴重地犯了我認為一個人所能犯的最大罪行,他應該對於由於政府的瓦解使一個國家遭受流血、掠奪和殘破等一切禍害負責。誰做了這樣的事,誰就該被認為是人類的公敵大害,而且應該受到相應的對待。」(第230條)

I grant, that the pride, ambition, and turbulence of private men have sometimes caused great disorders in commonwealths, and factions have been fatal to states and kingdoms. But whether the mischief hath oftener begun in the people’s wantonness, and a desire to cast off the lawful authority of their rulers, or in the rulers insolence, and endeavours to get and exercise an arbitrary power over their people; whether oppression, or disobedience, gave the first rise to the disorder, I leave it to impartial history to determine. This I am sure, whoever, either ruler or subject, by force goes about to invade the rights of either prince or people, and lays the foundation for overturning the constitution and frame of any just government, is highly guilty of the greatest crime, I think, a man is capable of, being to answer for all those mischief of blood, rapine, and desolation, which the breaking to pieces of governments bring on a country. And he who does it, is justly to be esteemed the common enemy and pest of mankind, and is to be treated accordingly. (Art. 230)

「如果在法律沒有規定或有疑義而又關係重大的事情上,君主和一部分人民之間發生了糾紛,我以為在這種場合的適當仲裁者應該是人民的集體。因為在君主受了人民的委託而又不受一般的普通法律規定的拘束的場合,如果有人覺得自己受到損害,以為君主的行為辜負了委託或超過了委託的範圍,那麼除了人民的集體(最初是由他們委託他的)以外,誰能最適當地判斷當初的委託範圍呢?但是,如果君主或任何執政者拒絕這種解決爭議的方法,那就只有訴諸上天。如果使用強力的雙方在世間缺乏公認的尊長或情況不容許訴諸世間的裁判者,這種強力正是一種戰爭狀態,在這種情況下,就只有訴諸上天。在這情況下,受害的一方必須自行判斷什麼時候他認為宜於使用這樣的申訴並向上天呼籲。」(第242條)

If a controversy arise betwixt a prince and some of the people, in a matter where the law is silent, or doubtful, and the thing be of great consequence, I should think the proper umpire, in such a case, should be the body of the people: for in cases where the prince hath a trust reposed in him, and is dispensed from the common ordinary rules of the law; there, if any men find themselves aggrieved, and think the prince acts contrary to, or beyond that trust, who so proper to judge as the body of the people, (who, at first, lodged that trust in him) how far they meant it should extend? But if the prince, or whoever they be in the administration, decline that way of determination, the appeal then lies no where but to heaven; force between either persons, who have no known superior on earth, or which permits no appeal to a judge on earth, being properly a state of war, wherein the appeal lies only to heaven; and in that state the injured party must judge for himself, when he will think fit to make use of that appeal, and put himself upon it. (Art. 242)

在這個紛紛擾擾的時刻,閱讀洛克的政府論卻著實讓人覺得「人家的著作可以在三百一十七年就點名清楚現在的情形,果然是有其在學術上的權威性!」這其實也不算是預言,只是很清楚地點明政府以及人民之間的權利、義務關係。在政府論的上篇,洛克主要是對抗「君權神授」的理論;在下篇之中,洛克則在闡揚自然權利、社會契約、政治體制和自由法治等思想理論。我把下篇十九章的目錄列出來:

1. (承接上篇,開始敘述政治權力。)

2. 論自然狀態

3. 論戰爭狀態

4. 論奴役

5. 論財產

6. 論父權

7. 論政治的或公民的社會

8. 論政治社會的起源

9. 論政治社會和政府的目的

10. 論國家的形式

11. 論立法權的範圍

12. 論國家的立法權、執法權和對外權

13. 論國家權力的統屬

14. 論特權

15. 綜論父權、政治權力和專制權力

16. 論征服

17. 論篡奪

18. 論暴政

19. 論政府的解體

這一連串看下來,有點頭昏眼花了吧!我們直接跳進最後一章去看,倒是可以看見許多會讓人不覺莞爾的會心微笑。之前,不是有某某黨的黨主席說了,如果誰誰誰被罷免下台,國家會亂嗎?我們可愛的洛克先生在三百一十七年前就已經賞了這個某某黨的黨主席一個甜蜜的耳光。(所以那位某某黨的黨主席好像應該要回家去唸唸書才對。)某位創造出「轉型正義」的偉大人士的論點也可以直接在這裡被洛克先生教訓一頓。(看來也是可以套句陳文茜以前常說的話,「回去唸唸書再來說吧!」)

所以說,如果歐美的民主素養在三百年前開始締造,經過了這些時間發展,終於建設出來一個還算有模有樣的格局;那麼我們的民主素養需要怎樣鍛鍊才能夠「趕美超英」呢?這其實真的是教育和民族性格養成的大問題!

現在台灣倒扁的活動正熱,據說大家都用「你匯了一百元了嗎?」來當問候語了!(真的還假的呀?)不過,當我在BBS上有樣學樣,這樣問候看我個人版面的朋友的時候,倒還沒有誇張到每個人都義憤填膺地去匯了款。對於我這個拿中華民國台灣護照,按照中華民國的稅法繳中華民國所得稅,享有中華民國公民權的人,我倒覺得不管匯不匯一百元,倒扁還是挺扁,都應該要把自己論述的來龍去脈整理清楚。(也就是說,如果只是一時氣憤只跟著別人大喊倒扁還是挺扁的人,不如拿一百元去買本政府論次講來好好充實一下所謂的「民主素養」還比較划算!真的,誠品網路書店裡,正港資訊文化事業有限公司出版的「洛克:政府論次講」才索價新台幣一百一十七元而已!)

如果要看免錢版的,孤狗大神也有求必應呀!

中文:http://easysea.net/zongjiao/luoke-zfl/index.htm (瞿菊農、葉啟芳譯本)

英文:http://www.constitution.org/jl/2ndtreat.htm

我摘錄一些讓我看的會心一笑的地方吧!(不過,先說一聲,以下可是很知青自high地摘錄自中文譯本和英文版本喔!)

「公民社會是它的成員之間的一種和平狀態,由於他們有立法機關作為仲裁者來解決可能發生於他們任何人之間的一切爭執,戰爭狀態就被排除了;因此,一個國家的成員是通過立法機關才聯合並團結成為一個協調的有機體的。立法機關是給予國家以形態、生命和統一的靈魂;分散的成員因此才彼此發生相互的影響、同情和聯繫。所以,當立法機關被破壞或解散的時候,隨之而來的是解體和消亡。因為,社會的要素和結合在於有一個統一的意志,立法機關一旦為大多數人所建立時,它就使這個意志得到表達,而且還可以說是這一意志的保管者。」(第212條)

Civil society being a state of peace, amongst those who are of it, from whom the state of war is excluded by the umpirage, which they have provided in their legislative, for the ending all differences that may arise amongst any of them, it is in their legislative, that the members of a commonwealth are united, and combined together into one coherent living body. This is the soul that gives form, life, and unity, to the common-wealth: from hence the several members have their mutual influence, sympathy, and connexion: and therefore, when the legislative is broken, or dissolved, dissolution and death follows: for the essence and union of the society consisting in having one will, the legislative, when once established by the majority, has the declaring, and as it were keeping of that will. (Art. 212)

「人們參加社會的理由在於保護他們的財產;他們選擇一個立法機關並授以權力的目的,是希望由此可以制定法律、樹立準則,以保衛社會一切成員的財產,限制社會各部分和各成員的權力並調節他們之間的統轄權。因為決不能設想,社會的意志是要使立法機關享有權力來破壞每個人想通過參加社會而取得的東西,以及人民為之使自己受制於他們自己選任的立法者的東西;所以當立法者們圖謀奪取和破壞人民的財產或貶低他們的地位使其處於專斷權力下的奴役狀態時,立法者們就使自己與人民處於戰爭狀態,人民因此就無需再予服從,而只有尋求上帝給予人們抵抗強暴的共同庇護。所以,立法機關一旦侵犯了社會的這個基本準則,並因野心、恐懼、愚蠢或腐敗,力圖使自己握有或給予任何其他人以一種絕對的權力,來支配人民的生命、權利和產業時,他們就由於這種背棄委託的行為而喪失了人民為了極不相同的目的曾給予他們的權力。這一權力便歸屬人民,人民享有恢復他們原來的自由的權利,並通過建立他們認為合適的新立法機關以謀求他們的安全和保障,而這些正是他們所以加入社會的目的。我在這裏所說的一般與立法機關有關的話也適用於最高的執行者,因為他受了人民的雙重委託,一方面參與立法機關又同時擔任法律的最高執行者,因此當他以專斷的意志來代替社會的法律時,他的行為就違背了這兩種委託。

假使他運用社會的強力、財富和政府機構來收買代表,使他們服務於他的目的,或公然預先限定選民們要他們選舉他曾以甘言、威脅、諾言或其他方法收買過來的人,並利用他們選出事前已答應投什麼票和制定什麼法律的人,那麼他的行為也違背了對他的委託。這種操縱候選人和選民並重新規定選舉方法的行為,豈不就是意味著從根本上破壞政府和毒化公共安全的本源嗎?因為,既然人民為自己保留了選擇他們的代表的權利,以保障他們的財產,他們這樣做不過是為了經常可以自由地選舉代表,而且被選出的代表按照經過審查和詳盡的討論而確定的國家和公共福利的需要,可以自由地作出決議和建議。那些在未聽到辯論並權衡各方面的理由以前就進行投票的人們,是不能做到這一點的。佈置這樣的御用議會,力圖把公然附和自己意志的人們來代替人民的真正代表和社會的立法者,這肯定是可能遇到的最大的背信行為和最完全的陰謀危害政府的表示。如果再加上顯然為同一目的而使用酬賞和懲罰,並利用歪曲法律的種種詭計,來排除和摧毀一切阻礙實行這種企圖和不願答應和同意出賣他們的國家的權利的人們,這究竟是在幹些什麼,是無可懷疑的了。

這些人用這樣的方式來運用權力,辜負了社會當初成立時就賦予的信託,他們在社會中應具有哪種權力,是不難斷定的;並且誰都可以看出,凡是曾經試圖這樣做的人都不會再被人所信任。」(第222條)

The reason why men enter into society, is the preservation of their property; and the end why they choose and authorize a legislative, is, that there may be laws made, and rules set, as guards and fences to the properties of all the members of the society, to limit the power, and moderate the dominion, of every part and member of the society: for since it can never be supposed to be the will of the society, that the legislative should have a power to destroy that which every one designs to secure, by entering into society, and for which the people submitted themselves to legislators of their own making; whenever the legislators endeavour to take away, and destroy the property of the people, or to reduce them to slavery under arbitrary power, they put themselves into a state of war with the people, who are thereupon absolved from any farther obedience, and are left to the common refuge, which God hath provided for all men, against force and violence. Whensoever therefore the legislative shall transgress this fundamental rule of society; and either by ambition, fear, folly or corruption, endeavour to grasp themselves, or put into the hands of any other, an absolute power over the lives, liberties, and estates of the people; by this breach of trust they forfeit the power the people had put into their hands for quite contrary ends, and it devolves to the people, who have a right to resume their original liberty, and, by the establishment of a new legislative, (such as they shall think fit) provide for their own safety and security, which is the end for which they are in society. What I have said here, concerning the legislative in general, holds true also concerning the supreme executor, who having a double trust put in him, both to have a part in the legislative, and the supreme execution of the law, acts against both, when he goes about to set up his own arbitrary will as the law of the society. He acts also contrary to his trust, when he either employs the force, treasure, and offices of the society, to corrupt the representatives, and gain them to his purposes; or openly pre-engages the electors, and prescribes to their choice, such, whom he has, by solicitations, threats, promises, or otherwise, won to his designs; and employs them to bring in such, who have promised before-hand what to vote, and what to enact. Thus to regulate candidates and electors, and new-model the ways of election, what is it but to cut up the government by the roots, and poison the very fountain of public security? for the people having reserved to themselves the choice of their representatives, as the fence to their properties, could do it for no other end, but that they might always be freely chosen, and so chosen, freely act, and advise, as the necessity of the common-wealth, and the public good should, upon examination, and mature debate, be judged to require. Thus, those who give their votes before they hear the debate, and have weighed the reasons on all sides, are not capable of doing. To prepare such an assembly as this, and endeavour to set up the declared abettors of his own will, for the true representatives of the people, and the law-makers of the society, is certainly as great a breach of trust, and as perfect a declaration of a design to subvert the government, as is possible to be met with. To which, if one shall add rewards and punishments visibly employed to the same end, and all the arts of perverted law made use of, to take off and destroy all that stand in the way of such a design, and will not comply and consent to betray the liberties of their country, it will be past doubt what is doing. What power they ought to have in the society, who thus employ it contrary to the trust went along with it in its first institution, is easy to determine; and one cannot but see, that he, who has once attempted any such thing as this, cannot any longer be trusted. (Art. 222)

「這種革命不是在稍有失政的情況下就會發生的。對於統治者的失政、一些錯誤的和不適當的法律和人類弱點所造成的一切過失,人民都會加以容忍,不致反抗或口出怨言的。但是,如果一連串的濫用權力、瀆職行為和陰謀詭計都殊途同歸,使其企圖為人民所了然——人民不能不感到他們是處於怎樣的境地,不能不看到他們的前途如何——則他們奮身而起,力圖把統治權交給能為他們保障最初建立政府的目的的人們,那是毫不足怪的。如果沒有這些目的,則古老的名稱和美麗的外表都決不會比自然狀態或純粹無政府狀態來得好,而是只會壞得多,一切障礙都是既嚴重而又咄咄逼人,但是補救的辦法卻更加遙遠和難以找到。」(第225條)

Such revolutions happen not upon every little mismanagement in public affairs. Great mistakes in the ruling part, many wrong and inconvenient laws, and all the slips of human frailty, will be born by the people without mutiny or murmur. But if a long train of abuses, prevarications and artifices, all tending the same way, make the design visible to the people, and they cannot but feel what they lie under, and see whither they are going; it is not to be wondered, that they should then rise themselves, and endeavour to put the rule into such hands which may secure to them the ends for which government was at first erected; and without which, ancient names, and specious forms, are so far from being better, that they are much worse, than the state of nature, or pure anarchy; the inconveniencies being all as great and as near, but the remedy farther off and more difficult. (Art. 225)

「但是,如果那些認為我的假設會造成叛亂的人的意思是:如果讓人民知道,當非法企圖危及他們的權利或財產時,他們可以無須服從,當他們的官長侵犯他們的財產、辜負他們所授與的委託時,他們可以反抗他們的非法的暴力,這就會引起內戰或內部爭吵;因此認為這一學說既對世界和平有這種危害性,就是不可容許的。如果他們抱這樣的看法,那麼,他們也可以根據同樣的理由說,老實人不可以反抗強盜或海賊,因為這會引起紛亂或流血。在這些場合倘發生任何危害,不應歸咎於防衛自己權利的人,而應歸罪於侵犯鄰人的權利的人。假使無辜的老實人必須為了和平乖乖地把他的一切放棄給對他施加強暴的人,那我倒希望人們設想一下,如果世上的和平只是由強暴和掠奪所構成,而且只是為了強盜和壓迫者的利益而維持和平,那麼世界上將存在什麼樣的一種和平。當羔羊不加抵抗地讓兇狠的狼來咬斷它的喉嚨,誰會認為這是強弱之間值得贊許的和平呢?」(第228條)

But if they, who say it lays a foundation for rebellion, mean that it may occasion civil wars, or intestine broils, to tell the people they are absolved from obedience when illegal attempts are made upon their liberties or properties, and may oppose the unlawful violence of those who were their magistrates, when they invade their properties contrary to the trust put in them; and that therefore this doctrine is not to be allowed, being so destructive to the peace of the world: they may as well say, upon the same ground, that honest men may not oppose robbers or pirates, because this may occasion disorder or bloodshed. If any mischief comes in such cases, it is not to be charged upon him who defends his own right, but on him that invades his neighbours. If the innocent honest man must quietly quit all he has, for peace sake, to him who will lay violent hands upon it, I desire it may be considered, what a kind of peace there will be in the world, which consists only in violence and rapine; and which is to be maintained only for the benefit of robbers and oppressors. Who would not think it an admirable peace betwixt the mighty and the mean, when the lamb, without resistance, yielded his throat to be torn by the imperious wolf? (Art. 228)

「我承認,私人的驕傲、野心和好亂成性有時曾引起了國家的大亂,黨爭也曾使許多國家和王國受到致命的打擊。但禍患究竟往往是由於人民的放肆和意欲擺脫合法統治者的權威所致,還是由於統治者的橫暴和企圖以專斷權力加諸人民所致,究竟是壓迫還是抗命最先導致混亂,我想讓公正的歷史去判斷。我相信,不論是統治者或臣民,只要用強力侵犯君主或人民的權利,並種下了推翻合法政府的組織和結構的禍根,他就嚴重地犯了我認為一個人所能犯的最大罪行,他應該對於由於政府的瓦解使一個國家遭受流血、掠奪和殘破等一切禍害負責。誰做了這樣的事,誰就該被認為是人類的公敵大害,而且應該受到相應的對待。」(第230條)

I grant, that the pride, ambition, and turbulence of private men have sometimes caused great disorders in commonwealths, and factions have been fatal to states and kingdoms. But whether the mischief hath oftener begun in the people’s wantonness, and a desire to cast off the lawful authority of their rulers, or in the rulers insolence, and endeavours to get and exercise an arbitrary power over their people; whether oppression, or disobedience, gave the first rise to the disorder, I leave it to impartial history to determine. This I am sure, whoever, either ruler or subject, by force goes about to invade the rights of either prince or people, and lays the foundation for overturning the constitution and frame of any just government, is highly guilty of the greatest crime, I think, a man is capable of, being to answer for all those mischief of blood, rapine, and desolation, which the breaking to pieces of governments bring on a country. And he who does it, is justly to be esteemed the common enemy and pest of mankind, and is to be treated accordingly. (Art. 230)

「如果在法律沒有規定或有疑義而又關係重大的事情上,君主和一部分人民之間發生了糾紛,我以為在這種場合的適當仲裁者應該是人民的集體。因為在君主受了人民的委託而又不受一般的普通法律規定的拘束的場合,如果有人覺得自己受到損害,以為君主的行為辜負了委託或超過了委託的範圍,那麼除了人民的集體(最初是由他們委託他的)以外,誰能最適當地判斷當初的委託範圍呢?但是,如果君主或任何執政者拒絕這種解決爭議的方法,那就只有訴諸上天。如果使用強力的雙方在世間缺乏公認的尊長或情況不容許訴諸世間的裁判者,這種強力正是一種戰爭狀態,在這種情況下,就只有訴諸上天。在這情況下,受害的一方必須自行判斷什麼時候他認為宜於使用這樣的申訴並向上天呼籲。」(第242條)

If a controversy arise betwixt a prince and some of the people, in a matter where the law is silent, or doubtful, and the thing be of great consequence, I should think the proper umpire, in such a case, should be the body of the people: for in cases where the prince hath a trust reposed in him, and is dispensed from the common ordinary rules of the law; there, if any men find themselves aggrieved, and think the prince acts contrary to, or beyond that trust, who so proper to judge as the body of the people, (who, at first, lodged that trust in him) how far they meant it should extend? But if the prince, or whoever they be in the administration, decline that way of determination, the appeal then lies no where but to heaven; force between either persons, who have no known superior on earth, or which permits no appeal to a judge on earth, being properly a state of war, wherein the appeal lies only to heaven; and in that state the injured party must judge for himself, when he will think fit to make use of that appeal, and put himself upon it. (Art. 242)

全站熱搜

留言列表

留言列表